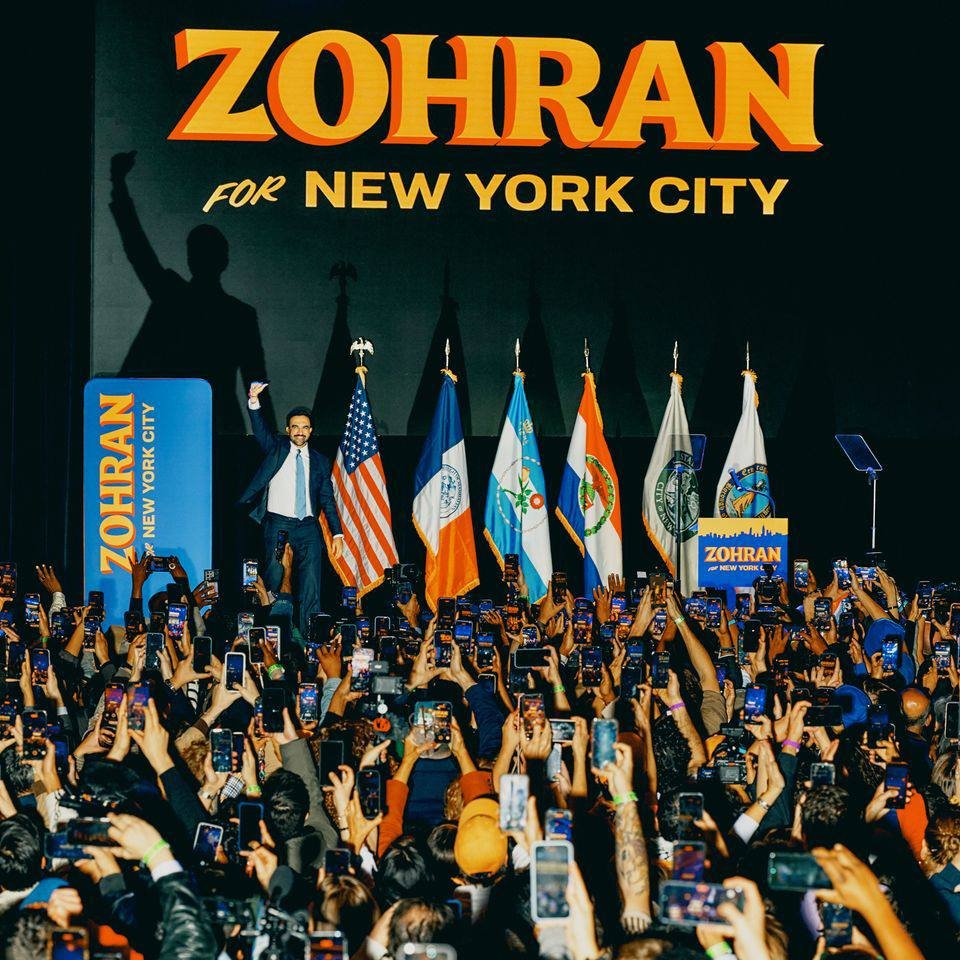

On November 4, 2025 or early morning of 5 November 2025 (IST), New York City voters delivered a resounding democratic mandate that echoes far beyond American shores. Zohran Mamdani’s election as the city’s first Muslim mayor, at just 34 years old, represents not merely a political victory but a profound statement about the direction of democratic values in an era marked by sustained campaigns of anti-Muslim sentiment across Western capitals and beyond. His triumph over former Governor Andrew Cuomo and Republican Curtis Sliwa, achieved with over one million votes and record-breaking turnout among young and working-class voters, demonstrates that despite systematic attempts to weaponize religious identity against political candidates, democratic publics retain the capacity to choose substantive governance over sectarian fear-mongering.

The electoral landscape leading to Mamdani’s victory was deliberately poisoned by anti-Muslim rhetoric. President Donald Trump explicitly branded Mamdani a “Communist” and threatened to cut federal funding to New York City if voters elected him, weaponizing religious identity as a proxy for ideological opposition. This pattern mirrors the documented institutional Islamophobia that has become increasingly normalized across Western political discourse. The Trump administration, which Mamdani now must navigate, had previously championed policies explicitly designed to target Muslim communities, from the travel ban affecting predominantly Muslim nations to proposals for surveillance programs targeting American Muslims and calls for closing mosques. Such rhetoric and policies have created an environment where Muslim political candidates face disproportionate scrutiny and delegitimization, branded with accusations of extremism and terrorism regardless of their records or positions.

Mamdani’s biography itself challenges the xenophobic narratives that have come to define anti-Muslim political campaigns in the West. Born in Kampala, Uganda, in 1991, he represents the cosmopolitan heritage of contemporary multiculturalism. His father, Mahmood Mamdani, is a renowned academic and professor of government and anthropology at Columbia University, a Gujarati Muslim born in Bombay and raised primarily in Uganda. His mother, filmmaker Mira Nair, is a Punjabi Hindu born in Rourkela and raised in Bhubaneswar, an Oscar-nominated director whose work centers overlooked perspectives and South Asian narratives. This heritage bridging Hindu-Muslim identity, African and South Asian connections, and intellectual commitment to social justice embodies precisely the pluralistic, cosmopolitan values that right-wing political movements across the West have systematically attacked. Yet it is these very qualities that resonated with New York’s voters, suggesting that fear based politics may finally be encountering democratic resistance.

The trajectory of anti-Islamic campaigns in Western democracies reveals a troubling institutional pattern. In Britain, London’s Muslim Mayor Sadiq Khan has endured relentless vilification since his election in 2016, facing not merely political opposition but explicit Islamophobic attacks. Conservative candidates have circulated leaflets linking Khan to extremism without credible evidence, while opposition figures spread baseless conspiracies about Islamic governance. When Khan was knighted in 2025 for his service, conservative media outlets denounced the honor with unveiled Islamophobic language, while simultaneously celebrating the elevation of anti-Khan Conservative candidates, including those who had run explicitly discriminatory campaigns to life peerages (In the UK, a life peerage is a noble title, such as “Baron” or “Baroness” granted for the person’s lifetime, giving them the right to sit in the House of Lords). Most recently, President Trump, speaking at the United Nations in September 2025, falsely accused Khan of attempting to impose Sharia law in London, prompting Khan to characterize Trump as “racist, sexist, misogynistic, and Islamophobic.” This escalating rhetoric exposes how anti-Muslim sentiment has become embedded not merely in fringe movements but in the mainstream political language of Western leaders.

The statistics on anti-Muslim sentiment across the West paint a sobering picture of institutionalized prejudice. In the United Kingdom, recorded anti-Muslim hate incidents reached 6,313 cases in 2024, a 43 percent increase from the previous year, the highest levels since monitoring began. This surge reflects not mere individual prejudice but coordinated campaigns of delegitimization. Research on the 2025 German federal elections reveals how mainstream political parties systematically weaponized anti-Islamic rhetoric in their official campaign manifestos and social media, portraying Muslims through lenses of terrorism, radicalization, and security threat. The Democratic, Christian Democratic, and Liberal parties constructed political narratives positioning Islam itself as a governance problem requiring state intervention and monitoring. Such institutionalized Islamophobia across Europe’s supposedly liberal democracies demonstrates that anti-Muslim hostility is not marginal but central to contemporary Western politics.

In the United States, polling data shows the partisan character of anti-Muslim sentiment, with a 2018 analysis revealing that 72 percent of Republicans surveyed associated Islam with violence, while 68 percent claimed Islam was incompatible with mainstream American society. Online harassment amplifies these sentiments: during the 2018 midterm elections, Muslim candidates reported facing disproportionate Islamophobic attacks through digital platforms, facilitated by influential anti-Muslim accounts that shaped narratives far beyond their actual constituency. The Trump administration’s policies—the travel ban, surveillance proposals, mosque closure rhetoric—translated this sentiment into governmental action, creating a climate where Muslim identity itself became politicized as a marker of national security threat rather than simply religious affiliation.

Against this backdrop of systematic anti-Muslim campaigns, New York’s voters chose differently. Mamdani’s platform centered working-class material demands: rent stabilization, free transit, universal childcare, affordable grocery access through city-operated stores, and taxation of corporations and the ultra wealthy. These substantive policy commitments attracted unprecedented voter engagement, particularly among young people and South Asian voters who recognized in Mamdani’s democratic socialism a direct challenge to the economic inequalities that define contemporary urban life. His victory suggests that democratic publics may prioritize material welfare and genuine governance over the manufactured fear that has driven so much recent electoral politics.

During his victory speech, Mamdani quoted Nehru. This triumph acquires deeper significance when understood through the lens of South Asian and postcolonial thought, particularly the secular, pluralistic vision articulated by Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, constructed a nation building project explicitly predicated on the principle that postcolonial democracy must transcend religious majoritarian logic. In 1947, faced with the devastation of Partition—violence explicitly mobilized through Hindu-Muslim communal identities—Nehru insisted that newly independent India could not permit such divisions to calcify into permanent governmental logic. He refused to allow the Muslim League’s separatism to justify the political marginalization of India’s Muslim citizens within an ostensibly Hindu nation-state. Instead, Nehru articulated a vision of secular democratic governance in which religious identity remained a matter of private conscience while public institutions and citizenship remained fundamentally non-sectarian.

But in reality contemporary Indian politics has fundamentally repudiated Nehru’s vision, with various political factions seeking to recast the Indian state as inherently Hindu and treating Muslim citizens with varying degrees of marginalization. This communalization of Indian governance has proceeded precisely through attacks on Nehru himself, his commitment to secularism, his support for minority rights, his resistance to communal politics—dismissed as “appeasement” by Hindu nationalists seeking to dismantle Nehruvian institutions. Yet Nehru’s relevance persists, paradoxically strengthened by these attacks. His arguments against communal politics, his insistence that genuine democracy must protect minorities, his vision of education and scientific development as forces for national integration—these principles seem increasingly urgent precisely as they are under assault.

Mamdani’s election invokes Nehruvian principles in a Western democratic context. Like Nehru’s vision for postcolonial India, Mamdani’s campaign rejected the notion that religious identity should determine political fitness. His victory affirms that democratic majorities can choose secular, pluralistic governance even in moments of sustained anti-Muslim propaganda. The parallel extends further: Nehru constructed his nation building project on the basis of working-class welfare, public investment in education and infrastructure, and principled secularism. Mamdani campaigns on precisely analogous commitments, affordable housing, free transit, universal childcare, and secular democratic governance despite religious identity. Both represent visions of democratic politics organized around material welfare rather than sectarian mobilization.

The international resonance of Mamdani’s victory thus operates on multiple registers. It demonstrates that democratic electorates can resist manufactured religious antagonism. It shows that working class material demands retain mobilizing power despite decades of political distraction through cultural warfare. And it affirms that figures of South Asian heritage, positioned at intersections of religious and cultural identity, can articulate political visions that transcend the communal logic that has fractured both postcolonial nations and Western democracies. That such a victory remains remarkable in 2025, that a secular democratic politician of Muslim faith can win office only against unprecedented anti-Muslim hostility, itself testifies to how profoundly Islamophobia has become institutionalized across Western political life.

In a nutshell, the stakes of Mamdani’s mayoral tenure extend beyond New York. His governance will either vindicate or refute the narrative central to contemporary right-wing politics: that Muslim political leaders represent inherent security threats incapable of serving non-Muslim constituents or managing secular institutions. In the context of sustained Western anti-Muslim sentiment—institutional, electoral, and rhetorical—Mamdani becomes a figure upon whom both progressive and reactionary movements project competing visions of democracy’s future. The young voters and working-class New Yorkers who elected him have indicated, at least in this moment, that they reject the premise that religious identity should determine political opportunity. That such a choice remains genuinely transgressive indicates how deeply anti-Muslim sentiment permeates Western political culture, and how significant any democratic refusal of that logic becomes. In choosing Mamdani, New York has chosen a vision of secular democracy aligned with Nehruvian principles—one organized around material welfare, pluralistic governance, and the fundamental democratic principle that citizenship transcends religious belonging.