The history of South Asia is filled with figures whose memory has oscillated between reverence and rejection, depending on the prevailing socio-political discourse, the legacies have been constantly renegotiated by successive generations. Some of these figures have been remembered through folk traditions, some through chronicles, and others through political myth-making. Among them, Sayyid Salar Masud Ghazi, popularly known as Ghazi Miyan, occupies a particularly contested place. For centuries, he has been venerated in popular memory and folk traditions across northern India. Yet, in contemporary political narratives, he is increasingly depicted as an invader and a symbol of religious aggression. Understanding him requires moving beyond the binaries of invader and hero, and instead appreciating the complexities of medieval statecraft, social memory, and historical representation, it is important to examine the development of his cult, the controversies that surround him, and the wider question of how Muslim rulers have been represented in Indian history.

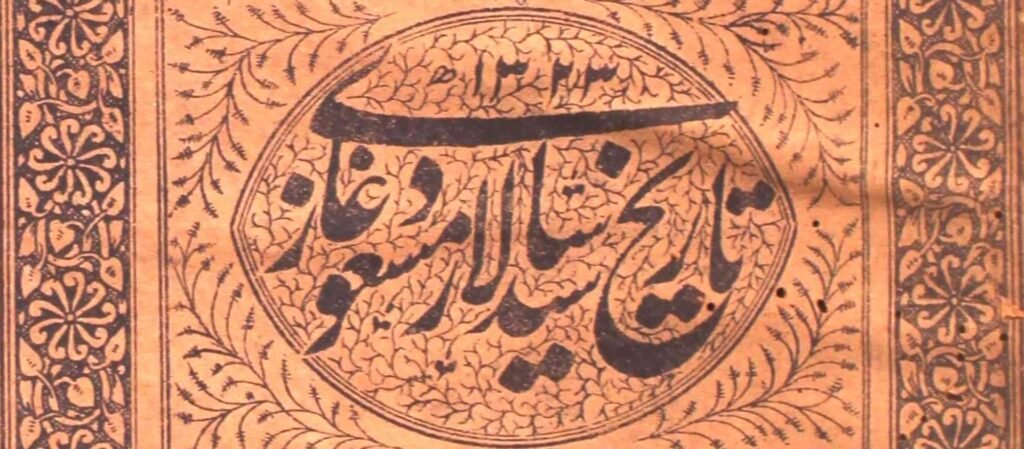

Sayyid Salar Masud Ghazi is traditionally believed to have been the nephew of Mahmud of Ghazni, though this claim is debated among historians. Some chronicles such as the Mirat-i-Masudi, composed in the seventeenth century, present him as a youthful warrior-saint who entered the Indian subcontinent during the early eleventh century and fought several battles in the region of present-day Uttar Pradesh. He is said to have been only in his late teens when he died in battle near Bahraich in 1034 CE. While others, including S.H. Hodivala in his studies of Indo-Persian sources, have suggested that Masud’s relationship with Mahmud was exaggerated in later hagiographies. The most famous account of his life, the Mirat-i-Masudi, was written much later in the seventeenth century by Abdur Rahman Chishti, long after the events it describes. Also, historian Richard Eaton notes in his work India’s Islamic Traditions, that figures like Masud represent the porous cultural exchanges between communities, where a warrior could be transformed into a saintly figure in popular devotion.

Despite uncertainties about the details of his biography, a broad consensus suggests that Masud came to northern India as a young warrior and was killed in battle around 1034 CE in Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh. He was likely no older than nineteen. His early death, combined with his association with military valour, facilitated his transformation into a figure of popular devotion.

After his death, Masud’s memory was enshrined in Bahraich, where his tomb became a shrine attracting pilgrims across religious boundaries. The annual Neja fair at Bahraich, centered around the raising of a ceremonial flag (neja), grew into one of the most significant folk gatherings in northern India. Devotees, both Hindu and Muslim, sang ballads in his praise, referring to him as “Balak Ghazi” (the boy warrior) who fought against injustice.

Historian Shahid Amin, in Event, Metaphor, Memory, documents how oral traditions around Ghazi Miyan survived and thrived for centuries, carried in the songs of rural women, balladeers, and Sufi performers. For many, Ghazi Miyan was less an invader and more a saintly protector who interceded on behalf of devotees, healed illnesses, and blessed marriages. This transformation from a historical figure into a folk saint illustrates the fluidity of memory in premodern societies, where distinctions between religion, politics, and spirituality were often blurred.

The reverence for Ghazi Miyan has not been without its critics. Because of his supposed relation with Mahmud of Ghazni, whose raids on Indian temples, especially the Somnath temple, remain etched in historical memory, Salar Masud is often portrayed as complicit in the same narrative of destruction. Critics argue that he, like his uncle, was an invader and a threat to Hindu society. In modern times, this has been amplified by political discourse that sees medieval Muslim rulers less as rulers embedded in Indian society and more as outsiders whose primary legacy is temple destruction and forced conversions.

Yet historians like Romila Thapar in her work Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History have shown that temple destruction was not a uniquely Muslim practice. Temples, as repositories of wealth and symbols of political sovereignty, were targeted by rival kings of all faiths. The Cholas raided Chalukyan temples; the Paramaras attacked rival shrines; even Maratha armies in the eighteenth-century plundered temples when it served strategic purposes. To single out Muslim rulers as uniquely “anti-Hindu” erases this broader context of medieval warfare.

In recent years, Ghazi Miyan has become the subject of cultural and political contestation. The annual Neja fair at Bahraich, which for centuries attracted large numbers of devotees, has faced restrictions. Reports suggest that the Uttar Pradesh government, under the rationale of law-and-order concerns, has sought to curb the fair, while certain right-wing groups have portrayed it as a remnant of “invader worship.” This reflects a broader trend where historical Muslim figures are recast as villains in contemporary identity politics.

The attempt to defame or diminish the legacy of Ghazi Miyan is part of a larger reimagining of Indian history where only select figures are celebrated while others are demonized. Yet oral traditions, folk songs, and the continued devotion at his dargah suggest that for many communities, he remains a beloved saint rather than an invader.

This reflects a wider attempt to rewrite India’s medieval past. By portraying Ghazi Miyan as a foreign aggressor, contemporary politics aligns with colonial-era narratives that emphasized a binary between “Hindu victims” and “Muslim oppressors.” Yet this narrative overlooks the fact that local communities, especially in Awadh and eastern Uttar Pradesh, have long venerated him irrespective of communal divisions. The persistence of folk songs and oral traditions testifies to a more syncretic historical memory that resists communal simplifications.

Central to Ghazi Miyan’s contested legacy is his battle with King Suhaildev of Shravasti. Folklore remembers Suhaildev as the king who killed Masud in 1034 CE, thereby halting the advance of Ghaznavid influence in the region. In modern nationalist discourse, this battle has been reframed as a Hindu king defeating a Muslim invader. However, historical evidence suggests that the conflict was less about religion and more about regional power struggles. Statues and memorials have been erected in his honour, and he has become a rallying figure in contemporary Uttar Pradesh politics.

As historian Shahid Amin has pointed out in his research on local traditions, the story of Suhaildev was largely revived and reshaped during the colonial and nationalist periods to construct a Hindu hero opposing Muslim aggression (Amin, 1997). This reframing strips the event of its original political context, where medieval rulers, regardless of religion, often fought for territory and supremacy rather than faith.

The question arises as to why Muslim rulers are persistently labelled as temple destroyers and invaders, while Hindu rulers who engaged in similar acts are rarely described in such terms. The Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, and even the Marathas carried out temple raids during periods of war. For example, the Cholas sacked the Chalukyan capital and plundered its temples, while the Paramara king Bhoja targeted rival shrines. For instance, the Rashtrakuta king Indra III destroyed the Kalapriya temple in Ujjain in the tenth century, while the Chola king Rajendra I looted temples in Bengal and Orissa. Even Vijayanagara kings, who are often celebrated as protectors of Hindu dharma, desecrated temples of their rivals. Historian Richard Davis in Lives of Indian Images documents how the desecration of temples was part of the political culture of medieval India.

This selective memory is not accidental. In the colonial period, British historians often emphasized Muslim temple destruction to portray Muslim rule as a dark age, in contrast to an imagined Hindu golden age. This narrative has persisted into postcolonial nationalist discourse, where it has been used to mobilize political sentiment. The vilification of Masud must also be understood within the broader selective memory of temple destruction. Yet in public discourse, only Muslim rulers are consistently remembered for such acts. This narrative has since been adopted by modern right-wing politics, which finds in it a convenient tool for communal mobilization.

Reducing Muslim rulers to the role of invaders obscures the extent to which they became integral to Indian society. The Mughals, for instance, adopted Persianate courtly traditions while also integrating Rajput nobles into their administration. Akbar’s policy of sulh-i kul (universal peace) symbolized an attempt to create a political order that transcended religious divisions.

Historians such as Satish Chandra and Irfan Habib have argued that the contribution of Muslim rulers to India’s agrarian expansion, urbanization, and cultural synthesis cannot be ignored. These rulers facilitated India’s transition into one of the largest agrarian economies of the early modern world, while also fostering composite cultural forms such as Hindustani music, Indo-Persian literature, and architectural masterpieces like the Taj Mahal, Red Fort, and many others.

The Delhi Sultans expanded irrigation networks and trade routes. And even Aurangzeb, often vilified in popular narratives, patronized Hindu temples such as the Mahakal temple in Ujjain while also imposing orthodox policies elsewhere, illustrating the contradictions of medieval statecraft. To view this legacy only through the lens of outsiders, and invaders is to flatten the richness of India’s past. To portray them simply as anti-Hindu is to distort the complexity of history.

A central puzzle remains. Why are only Muslim rulers remembered as invaders, while Hindu rulers who engaged in equally destructive practices are celebrated as protectors of dharma. The answer lies in the politics of memory. Muslim rulers, by virtue of their foreign origins, were easier to cast as outsiders, despite the fact that their descendants lived and died in India. Hindu rulers, even when destructive, could be absorbed into the national story as part of a continuous tradition.

Throughout India’s long history, numerous groups entered the subcontinent as outsiders, yet their legacy is rarely cast in terms of criminality or religious aggression. The Aryans, who migrated to the Indo-Gangetic plains around 1500 BCE, established new social and political orders, introducing the Vedic culture that shaped early Indian civilization. Centuries later, the Sakas (Scythians) and Kushans, originally Central Asian nomads, invaded and settled in northern and northwestern India, founding dynasties that ruled large territories, minted coins, patronized arts, and facilitated trade across Asia.

Similarly, the Huns in the fifth century CE entered India through violent campaigns, yet they are often remembered primarily in terms of their political impact rather than as “invaders” in a moral sense. Even the Greeks under Alexander briefly entered the subcontinent and left traces in coinage and urban culture. Historians such as Romila Thapar and Richard Eaton emphasize that invasion, conquest, and settlement were part of the broader patterns of state formation in India, and not uniquely tied to Muslim rulers (Thapar, 2002; Eaton, 2003). What differentiates Muslim rulers in popular and political discourse is not their foreign origin, but the selective memory that frames them as anti-Hindu, while these earlier outsiders are often integrated into the story of India’s evolving civilization.

This selective remembering has real consequences. By portraying Muslim rulers as perennial outsiders, modern politics seeks to delegitimize centuries of Muslim presence in India. Figures like Sayyid Salar Masud are particularly vulnerable to this rewriting, as their cults testify to a syncretic past that does not fit neatly into communal categories.

In a nutshell, the story of Sayyid Salar Masud Ghazi is more than the biography of a young warrior who died in battle. It is a story of how memory is constructed, reshaped, and contested over centuries. In popular devotion, he became Ghazi Miyan, a saint revered by both Hindus and Muslims. In colonial historiography, he became a symbol of foreign aggression. In contemporary politics, he is recast as an invader to be vilified. Each of these representations tells us less about Masud himself and more about the societies remembering him.

To see him only as an invader is to ignore the syncretic traditions that grew around his shrine, the songs that celebrate him as a folk hero, and the evidence that his battle with Suhaildev was about politics rather than religion. To reduce Muslim rulers to anti-Hindu destroyers is to forget the complexity of medieval warfare, where temples were political symbols targeted by all rulers, and to erase the contributions of Muslim dynasties to India’s economy, culture, and society.

History is rarely black and white. Figures like Ghazi Miyan remind us of the shades of grey that characterized India’s past. A balanced view neither glorifies nor vilifies but seeks to understand. The attempt to erase or vilify various Muslim figures is not just about history; it is about shaping the present. By denying the syncretic traditions that developed around such figures, contemporary politics risks flattening the diversity of India’s past into a simplistic tale of eternal Hindu-Muslim conflict. Historical scholarship reminds us that the reality is far more nuanced. A balanced view recognizes the violence and conflict of the past while also acknowledging the cultural synthesis and shared traditions that emerged from it. In times when history is mobilized for political gain, reclaiming this complexity is not only an academic task but a civic necessity.