Introduction

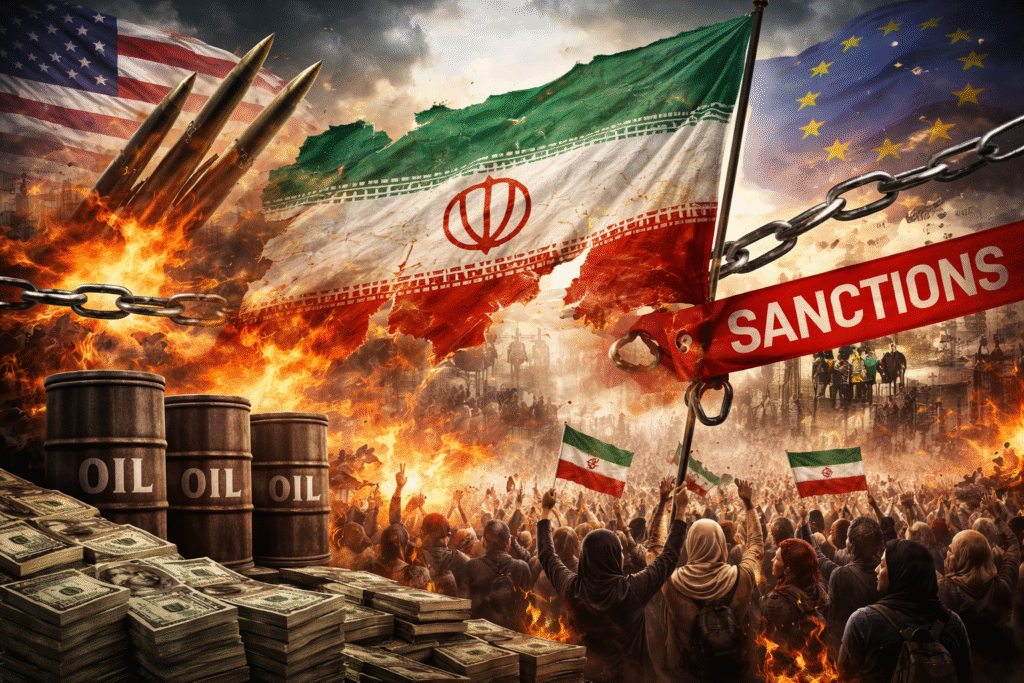

This article suggests that the 2026 Iran crisis is more than just recurring turmoil; it highlights a deeper issue of legitimacy unravelling, fueled by economic decline, rigid ideologies, and isolationist foreign policies. One of the significant concerns today is Iran’s internal disturbances marked by economic hardships, leading to larger public discontent among the citizens of Iran. These disturbances can be reflected in widespread protests where citizens’ demands for freedom in the larger decision-making process is concern. These internal issues have played a crucial and visible role in determining the national policies of iran reflecting their stances on key global issues. “The economic consequences of these foreign policy decisions, particularly the sanctions and embargoes imposed primarily by the United States, the European Union, the United Kingdom, and to a lesser extent by Canada and Australia, have had a profound impact on the Iranian populace. Economic challenges, combined with political repression, have led to increasing social unrest, pushing the country toward a critical juncture where the future direction of the state is uncertain.” (Abbasi, 2025). Here it is important to note that the theocratic regime has been in power since 1979, where there has been large dissent among the local population regarding the governance model of the regime. Even the partial picture helps people to understand the level of human rights violations citizens are going through within Iran. During the course of this crisis and larger protest, “Some 19,000 people have been arrested, according to HRANA, which says its data comes from on-the-ground sources and goes through multiple internal checks. Iran’s top judge has suggested that there needs to be rapid trials and executions to restore order. Eyewitness accounts are scant, and those who report on the situation usually do so anonymously for fear of reprisals.” (Smith & Babak Dehghanpisheh, 2026). “According to the Statistical Centre of Iran and World Bank data, inflation rates exceeded 45% in 2021–2022, and youth unemployment rates have remained above 25% in recent years, contributing to widespread discontent. In addition, documented protest data indicate more than 4000 incidents of civil unrest between 2017 and 2022, with key episodes such as the nationwide protests in 2019 and 2022 highlighting the population’s dissatisfaction with both economic conditions and governance.” (Abbasi, 2025). Moreover, Iran’s larger support to various non-state actors or so called terrorist has also tarnished the country’s image in a larger international forum, leading to various sanctions by the European Union, the United States, but more importantly, leading Iran to a larger isolationism in the larger decision-making process within the international community. This nature of isolationism in recent years has also led to larger political isolatism where Iran mainly relies on non-Western countries for its support, further culminating in various crises. Here, the stance of Iran on various issues has played a crucial role in its domestic economy, where it is important to note that Iran’s economy relies heavily on oil, with oil and gas contributing to 50 per cent of its economy. However, “the renewed tightening of sanctions since 2018 has further exposed this dependence, leading to an average inflation rate above 40% and a sharp decline in real wages, thereby eroding purchasing power and fueling social unrest. The economic stagnation has worsened social inequalities and increased the risk of social unrest. The study also shows a growing gap between the ruling elite and the general population.” (Abbasi, 2025). Reflected in the larger protest, the Iranian population largely demands regime change, where the demand for political change remains a strong voice, mainly in the urban centres.

While internal governance failures play a significant role, the persistence and severity of Iran’s inflationary crisis cannot be understood without recognising the central role of U.S. and Western economic sanctions, which have systematically eroded the state’s capacity to regulate prices, stabilise currency, and deliver welfare.

Nature of the Regime in Iran and the question of legitimacy

Although the regime gains its formal legitimacy from theocratic doctrines, to a large extent, it has relied on repressive state apparatuses, focusing on economic militarisation, to secure its dominance. Over time, the regime has maintained its authority through religious narratives and interpretations; however, it fails to address the broader social needs of the population. “This failure has led to widespread erosion of public trust and mounting dissatisfaction, particularly among younger generations and urban populations. “The regime’s reliance on political repression, including restrictions on freedom of expression, suppression of dissent, and imprisonment of opposition figures, has further aggravated internal tensions. The concentration of power in the hands of the Supreme Leader, coupled with the absence of genuine political pluralism, has effectively obstructed meaningful reform initiatives.”(Abbasi, 2025). A 2022 survey by the Group for Analysing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran GAMAAN found that nearly 90% of Iranians do not support the Islamic Republic as a system of governance. Additionally, 73% of respondents favour the separation of religion from politics—directly opposing the regime’s theocratic foundations. Calls for secular democracy and respect for human rights transcend ideological boundaries. Opposition comes from a wide range of constituencies—women’s rights activists, students, labourers, ethnic minorities, monarchists, secular republicans, and even traditional religious groups.” (Parsa, 2025). Over a period of time, the government itself has faced a larger legitimacy issue, where the government is finding difficulties in the implementation of the hijab law, as millions of Iranians openly oppose it. It has been seen that reform is no longer an option where the people themselves pose themselves as the greatest threat, more than external actors. The participation of people in elections has turned out to be significantly low. “ Independent research suggests actual turnout may have been closer to 20%. Years of tightly controlled elections, in which only regime-approved candidates can run, have rendered voting meaningless for most citizens. Each election cycle now reinforces cynicism rather than hope. What remains is a regime with no credible democratic mandate and a leadership structure that commands neither trust nor respect.” (Parsa, 2025). Massive protests have emerged during various courses of time, but the the simolutaneous dynamics of the contemporary proest makes the very nature unique. “First, the geography: protests are ubiquitous around the country. Second, the diversity of the protesters, who represent a wide range of Iranians. Third, there is some effort to rally around Reza Pahlavi, the shah’s son, who was overthrown by the Islamic Revolution in 1979.” (Aslı Aydıntaşbaş et al., 2026). In recent times, the Iranian government’s priority of security over all has been a particular point of tension for a long period of time. While the threat of attacks on Iran in 2024 and 2025 was a genuine concern, Iranian authorities were increasing their security and surveillance budgets long before conflict emerged from the Israel-Hamas War. These complaints were compounded by the passing of Jina Mahsa Amini, which initiated the Women, Life and Freedom demonstrations in 2022 and was widely believed to have been caused by an excessively aggressive police state and governmental neglect. Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian suggested an annual budget that reflected the imbalance, increasing security spending by almost 150 per cent and adding wage increases to only 26% of inflation. This was done at the beginning of the 2026 protests. By early January in 2026, people are engaged in a protest that erupted across 31 provinces, largely driven by economic concerns. The symbolism of the lion and the sun in the protests reflects the Iranian flag of the 15th century, reflecting a strong support towards the return of the monarchy. While many others view this symbolism as a symbol of resistance, demanding their support towards Iran before the 1970s, notable figures have raised their voices in support of the protests.

Sanctions, Inflation, and the Structural Economic Trap

A central and often underemphasised driver of Iran’s economic crisis is the cumulative impact of U.S.-led and Western economic sanctions, which have structurally constrained the state’s ability to manage inflation, stabilise currency, and pursue developmental policy. While domestic mismanagement and ideological rigidity have aggravated economic decline, sanctions have significantly reduced the Iranian government’s fiscal space and policy autonomy. Restrictions on oil exports, banking transactions, foreign investment, and access to global financial institutions—particularly following the U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018—have sharply curtailed state revenues and foreign exchange reserves.

These constraints have directly contributed to persistent inflationary pressures. With oil and gas accounting for nearly half of Iran’s national income, sanctions targeting the energy sector have reduced export volumes and earnings, weakening the rial and increasing import costs. As a result, the government has relied on deficit financing and monetary expansion to meet basic expenditure obligations, further accelerating inflation. The inability to access international credit markets or stabilisation mechanisms has rendered conventional inflation-control tools largely ineffective. Consequently, inflation exceeding 40% has become a structural condition rather than a cyclical shock, disproportionately affecting lower- and middle-income households.

Sanctions have also distorted labour markets and industrial productivity. Restrictions on technology transfers, capital goods, and international partnerships have weakened domestic manufacturing and increased unemployment, particularly among youth. While the regime has attempted to offset these pressures through closer economic ties with China, Russia, and regional actors, these relationships have offered limited relief and often operate on asymmetrical terms, reinforcing dependency rather than sustainable growth. Thus, sanctions have not merely punished the state; they have reshaped Iran’s political economy in ways that intensify social inequality, deepen public grievances, and undermine regime legitimacy.

Iran’s Foreign Policy

“The regime’s foreign policy has been characterised by a confrontational approach toward the West, while simultaneously seeking to cultivate strategic alliances with non-Western powers such as Russia and China.”(Abbasi, 2025). “Iran’s support to non state organization such as hezbollah along with an adversarial stance on Israel, has intensified the nature of confrontation within the larger international arena. These alliances with alternative global powers have provided limited economic relief but often at the cost of Iran’s autonomy and long-term development. Moreover, Iran’s nuclear ambitions have triggered international alarm, deepened mistrust and complicated diplomatic engagement. In recent years, the escalating confrontation between Iran and Israel has emerged as a central axis of regional instability.” (Abbasi, 2025). From Iran’s viewpoints these action highlights its sovereignty and security, but here it is important to note that the ideological battle of the regime against the West has led to the imposition of several sanctions on Iran, having significant impacts on the country’s welfare and development. While the nature of these sanctions is to prevent a larger nuclear threat , it has isolated Iran from the global economy, making it difficult for it to engage in trade and the development process. Nonetheless, the government has made efforts to lessen the impact. Improving sanctions by strengthening ties with countries such as China, Russia, and other regional powers. Nevertheless, these alliances haven’t been effective in neutralising the wider consequences of global isolation, leading to a delicate economy. The regime’s dependence on these external entities, along with its internal conflicts, highlights the fragility of Iran’s political and economic systems.

Conclusion

“The possibility of meaningful reform within the current political system remains uncertain. The regime’s centralisation of power, alongside its suppression of opposition, has hindered prospects for structural political change. Reform, as demanded by various segments of Iranian society, particularly the middle class, students, civil society actors, and women’s rights advocates, typically encompasses a broad range of expectations.” The demands have consolidated into the 2026 protests, which span all 31 provinces and unify diverse groups using symbols such as the lion and sun, serving as a widespread opposition to the theocratic model. As reflected by the GAMAAN survey conducted in 2022, almost 90% of Iranians are against the Islamic Republic, and 73% support the separation of religion and politics (Parsa, 2025). More than 4,000 unrest incidents since 2017 have been driven by inflation and youth unemployment above 25%, which are contributing to the crisis highlighted by economic indicators (Abbasi, 2025). Iran’s assertive foreign policy, which includes backing Hezbollah, nuclear aspirations, and alliances with Russia and China, has led to crippling sanctions that expose its oil-driven economy and deepen Iranian isolation. This crucial moment presents a threat to the regime’s survival.?… Repressive measures, such as 19,000 arrests and demands for swift executions (Smith & Babak Dehghanpisheh, 2026), can delay the collapse of society but do not bring back trust. Reza Pahlavi’s popularity and frequent demonstrations indicate that regime change is now a real possibility, as demonstrated by low voter turnout (around 20%) and hijab disobedience. Iran stands at a crossroads with numerous internal and external threats, where the path of Iran will be determined by the nature of the protest that will play a crucial role in understanding the larger narratives. “Whether Iran can overcome its current challenges and move toward a more democratic and prosperous future will depend on a complex interplay of domestic and international factors.” (Abbasi, 2025).

References

Abbasi, E. (2025). Political challenges and crisis management in the Islamic Republic of Iran: a comprehensive analysis. Discover Global Society, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-025-00247-9

Smith, A., & Babak Dehghanpisheh. (2026, January 16). Iran has a long history of violent suppression, but this time may be different. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/world/iran/iran-long-history-violent-suppression-time-may-different-rcna254361

Parsa, F. (2025, May 9). Why Regime Change in Iran Is Becoming Inevitable. RealClearDefense. https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2025/05/09/why_regime_change_in_iran_is_becoming_inevitable_1109125.html

Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, Feltman, J., Karlin, M., O’Hanlon, M. E., Grewal, S., Shibley Telhami, & Heydemann, S. (2026, January 15). Is Iran on the brink of change? Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/is-iran-on-the-brink-of-change/

Arnab’s core research interests lie in political engagement, digital activism, youth participation, and contemporary international relations, reflecting his commitment to understanding the evolving dynamics of politics both in India and globally..